Burundi is an East African country which has been affected by recurring political and ethnic violence since its independence in 1962. It was the scene of a crisis following the assassination of its first democratically elected president, Melchior Ndadaye, in 1993 (Nantulya, 2015). This event embarked the country back into a cycle of mass violence, claiming the lives of hundreds of thousands of people and displacing more than a million others. Faced with the intensification of the civil war in the years that followed, the regional and international community launched mediation efforts that led to the Arusha Peace Process. Initiated in 1996, the Arusha negotiations resulted in the signing of the Peace and Reconciliation Agreement for Burundi in August 2000 (Åberg, et al., 2008). This agreement aimed to end the violence, address the root causes of the conflict and establish a framework for democratic transition and reconciliation. However, achieving lasting peace has proven to be a long and difficult road, with a final ceasefire not being signed until 2008. The Arusha Process, although yielded some success, it has also been criticized for its design, management and outcome. This critical analysis aims to examine the dynamics of the Arusha Peace Process through interrelated factors: conflict-related factors, conflict ripeness, party-related factors and mediation-related factors.

To assess the Arusha peace process, it is important to understand the nature of the Burundian conflict. The conflict in Burundi gets its origine in the pre-independence era, marked by the political manipulation of ethnic and class differences, exacerbated by the Belgian colonial administration following a divide-and-rule approach (Åberg, et al., 2008). Burundi’s post-independence history was marked by episodes of massive violence in 1965, 1972, 1988 and especially between 1993 and 2003 (Bentley, 2004), which generally follow a pattern of Hutu insurgencies followed by repression by the Tutsi-dominated army. These cycles of violence have resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths and massive population displacement. The nature of the conflict is described by the Arusha Agreement itself as being characterized by issues of genocide and exclusion, and the parties reaffirm their determination to end the root causes underlying the recurring state of violence, bloodshed, insecurity, political instability, genocide and exclusion (Åberg, et al., 2008). This conflict is thus linked to identity issues as well as the struggle for power and access to resources between Burundian political-ethnic elites.

The intensity and duration of this conflict has occasioned a “hurting stalemate” for the parties. As Kleiboer (1996) metions, certain analysts consider that conflicts follow the logic of “clock time.” The more time goes in terms of years, months, the more this duration is more likely to change the attitudes of conflict parties toward the conflict. Following the Arusha negotiations in 1996, the parties had already reached a level of considerable human and economic cost of the war where the unilateral military efforts were viewed was no longer viewed by most conflict actors a solution but rather engaging in peaceful negotiations (Bentley, 2004). The neighboring states also played an important role to bring the conflict parties to this stage when these states imposed economic sanctions to Pierre Buyoya’s coup d’état in 1996 which led to external pressure that probably contributed to a “ripe moment” (Zartman, 2001) for negotiations. This approach led the parties to showcase their willingness to resolve the conflict through peaceful means. However, the Arusha negotiations did not immediately end armed conflicts. The continuation of fighting after the signing of the peace agreement was due to the absence of two of the main rebel groups, the CNDD-FDD and the Palipehutu-FNL, who did not sign the agreement initially even though their political wings were able to attend the talks (Åberg, et al., 2008). This situation implies that the conflict was not ripe enough for mediation even though most parties were ready to negotiate. The conflict was not ripe enough for these two parties, and this means that other options leading them to ripeness either through incentives or disincentives should have been explored.

The success of any peace process does require the engagement or willingness of all conflict parties to participate in the negotiations. The Arusha Process brought together 19 parties who signed the Peace and Reconciliation Agreement (Åberg, et al., 2008). These parties included political parties and some armed groups. The approach to this mediation has been described as inclusive as it involved many actors which was generally considered to increase the legitimacy and durability of the agreement. Even though there was a big number of actors participating. In this peace process including the Burundian People’s Rally (RPB) and the Union for National Progress (UPRONA), the Arusha process has also faced criticism and significant weakness as “not all armed rebel groups were involved in this peace agreement” (Åberg, et al., 2008). Specifically, the CNDD-FDD and the Palipehutu-FNL, did not sign the agreement. Although their political wings were able to attend the discussions, differences between the political and military wings of these movements led to a split, preventing the signing by the armed groups themselves, “the FNL and FDD, the two main armed Hutu rebel groups, were not parties to it, and some of the 19 parties felt that Mandela had bullied them into signing, which compromised their commitment and weakened the accord’s long-term prospects (Bentley, 2004, p. 73). This exclusion proved to be a cause of continued violence and large-scale displacement of people in the years following the signing of the Arusha Agreement.

Separate ceasefire agreements had to be negotiated with these groups after the Arusha Agreement, lasting from 2003 to 2008. The failure of the main process to include other main armed actors has clearly weakened its ability to immediately end hostilities. The Agreement itself acknowledges this shortcoming by specifically calling on the armed wings of the non-signatory parties to suspend hostilities and enter ceasefire negotiations. The issue of representation and decision-making power of negotiators is also raised in the context of African peace processes, including Arusha. While an inclusive process with many participants may be more legitimate, it may also be more difficult to manage, and effectiveness may depend on the actual decision-making power of delegates. But still, this process was “fairly successful” (Åberg, et al., 2008), as Burundi involved parties that were not necessarily democratically legitimized to have their place at the table. This reflects the pragmatic nature of peace negotiations in wartime, where the representation of real power on the ground (including military) is crucial, even if it is undemocratic.

Another important aspect of party-related factors is the internal cohesion of delegations. The split between the political and military wings of some groups illustrates a lack of internal cohesion that directly affected the outcome of the Arusha negotiations, since the armed groups did not ratify the agreement signed by their political counterparts. This showcases the importance for mediators to understand the internal dynamics of the parties and to ensure that negotiators have a clear mandate and the authority to engage their constituencies. Finally, the perception of the balance of power between the parties influences their willingness to make concessions. In the Burundian context, the Tutsi-dominated army held significant power. The power-sharing arrangements ultimately included in the agreement (60% Hutu and 40% Tutsi in government institutions, equal army) reflect a compromise aimed at balancing the interests and powers of the major groups (Vandeginste & Raffoul, 2023, p.2). However, for some rebel groups, these compromises may not have gone far enough or were perceived as unbalanced contributing to their initial rejection of the agreement.

Mediation factors are essential in understanding the course and success (or failure) of a peace process. In the case of Arusha, several aspects of mediation were involved; the identity and style of the mediators, the mediation strategy adopted and external support.

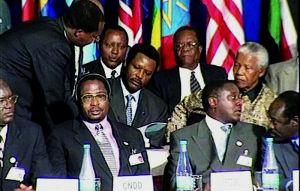

The Arusha Process was characterized by the presence of high-profile mediators such as: former Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere, followed by Nelson Mandela. These regional figures described as seasoned statesmen played a decisive role (Bentley, 2004). Their moral stature and experience strongly shaped the process. Nelson Mandela is described as having an “outspoken” (frank/direct) and “moral” role. Contrary to the Western notion of a “neutral” mediator, Mandela demonstrated how the moral authority of a facilitator can be used effectively (Åberg, et al., 2008, p.21). He notably used “moral pressure” to overcome blockages as evidenced by his visits to a prison and a refugee camp, where he publicly linked the release of political prisoners and the situation of refugees to peace. The effectiveness of these high-level mediators potentially contrasts with the more general criticism of African peace initiatives suffering from a lack of specialist expertise and insufficient institutional capacity. The presence of figures like Nyerere and Mandela, supported by a regional network and a facilitation team, may have compensated for some of these general institutional limitations.

The mediation strategy in Arusha combined several approaches. It was a regional mediation effort marked in 1996 by a fundamental decision of regional heads of state to impose economic sanctions on the Burundian government (Bentley, 2004). This use of sanctions by neighboring states represents a form of leverage or external pressure to push the parties towards negotiation, and this demonstrated an unusual regional determination and cohesion (Åberg, et al., 2008). The negotiation process itself was structured in a complex way. It comprised five committees dealing with key topics: the nature of conflict, democracy and good governance, peace and security, reconstruction and development, and implementation guarantees. This thematic structure made it possible to comprehensively address the different dimensions of the conflict. The facilitation team, consisting of “some two-dozen people” in addition to the main mediators, supported the work of the committees.

A key strategy employed by mediators was the use of a “draft text”. Even though this approach may expose mediators to biasness, it has proven useful in overcoming blockages and moving talks forward (Åberg, et al., 2008). The process of working on this project was characterized by an important rule: the parties could only change the content if there was full consensus, thus encouraging them to negotiate and compromise with each other (“If you change this, I’ll let you change that”) (Åberg, et al., 2008). This work on the draft took about a year, which fairly demonstrates a patient and deliberate process of adaptation of the text by the parties with the support of the mediators. This model contrasts with the criticism of the Darfur process where an agreement was drafted by the mediators, the African Union presented to the parties on a “take it or leave it” basis with a very short timeframe and this led to a lack of ownership by the parties (Nathan, 2006, p.7 ). In the case of Arusha, the fact that the parties had sufficient time to adapt the draft fostered a sense of ownership, even if it was not total. The mediation style in Arusha is described as combining directive and non-directive approaches, depending on the phase and the problem (Åberg, et al., 2008). Nyerere and Mandela used moral pressure, but the mediators also formulated draft texts, which falls under “formulative” or even “manipulative/directive” mediation depending on the typologies. The effectiveness of these directive approaches depends on their acceptance by the parties (Bentley, 2004).

The Arusha Process benefited from the support of various international actors, including the United Nations, the Organization of African Unity (OAU, predecessor of the AU), the European Union, and the Mwalimu Nyerere Foundation, which affixed their signatures as witnesses and expressions of moral support. However, there have been critics that this process suffered from the lack of sufficient Western support for regional initiatives (sanctions and Nyerere’s mediation) (Åberg, et al., 2008,p.24). The Western perception of the need to work with moderates and ease sanctions was at odds with the Burundian government’s military policy, suggesting the need for more external pressure, orchestrated to include radical rebel groups. This tension between regional and Western approaches presents the various challenges of third-party coordination in African peace processes (Åberg, et al., 2008). The Agreement also provided for “Guarantees on the Implementation of the Agreement” recognizing that signing is only the first step and continued support is essential. The creation of an Implementation Monitoring Committee was planned, but initial disagreements over implementation, particularly on transitional justice, posed challenges.

The Arusha peace process involves various elements that contributed to its success such as a strong and committed regional leadership, a detailed and adaptive process design, institutional farmwork for power sharing as well as the resilience of the conflict parties. On the other hand, this mediation also did experience serious short coming which contributed to its ineffectiveness such as the exclusion of key armed groups in signing the peace agreement, lack of critical details and implementation mechanisms, challenges of representation and cohesion of the parties, and the dependence on external factors and tension in coordination.

The Arusha Peace Agreement became successful based on a few factors. First, this mediation process involved a strong and committed regional leadership. The decision by regional heads of state to impose sanctions and appoint high-caliber mediators like Nyerere and Mandela was a important contributing factor to the positive achievements resulted from this process. These countries sustained commitment, moral authority and their willingness to use levers (sanctions, moral pressure) that were crucial in moving the process forward, particularly in overcoming deadlocks and bringing the parties back to the table after Nyerere’s death (Åberg, et al., 2008).

Second, this mediation process employed a detailed and adaptive process that contributed to its success. The use of a draft text, developed with the support of mediators and modifiable by consensus of the parties over a long period, seems to have encouraged a certain level of appropriation by the signatories, even this would not necessarily yield positive results in other processes such as Darfur.

Third, the use of an institutional framework for power sharing proved to be successful in the case of Burundi. Even though there is no other country which has used this method regrading to ethnic groups according to Vandeginste & Raffoul (2023), setting quotas for Hutu and Tutsi representation in the government and army and civil society organizations seem to have maintained some level of stability in Burundi and prevent tragedies like the 1994 in genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda. Even though there have been civil wars and other violent uprise like in 2015, one could still argue that Burundi has managed to maintain internal and external security threats that could lead to armed conflicts as it is the case in the neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo. Lastly, conflict parties in this process also expressed resilience in face of challenges. The death of Julius Nyerere on the 14th of October 1999 as the major mediator in this conflict Julias Kambarage later replaced by Nelson Mandela in December (Åberg, et al., 2008) did not have a huge impact on the negotiation process as many people would have expected.

The most significant flaw in the Arusha Agreement was the failure to include the CNDD-FDD and Palipehutu-FNL, the most prominent armed rebel groups (Åberg, et al., 2008). This exclusion directly led to the continuation of violence after the signing of the agreement, undermining the immediate objective of cessation of hostilities and requiring subsequent and separate ceasefire negotiations that took several years until 2008 (Vandeginste & Raffoul, 2023). Although the agreement was comprehensive in its thematic scope, it did not cover some critical details and that power-sharing negotiations continued after the agreement. The question of implementation, including sensitive aspects such as transitional justice, also posed a problem, with the agreement sometimes delegating points to a later transformation process or lacking clarity on implementation mechanisms. The representation of parties also raised questions. The fact that the exclusion of armed groups was partly due to the split between the political and military wings caused problems of internal cohesion within the parties. One could argue that the nature of peace negotiations involving groups that have acquired their legitimacy through arms might have influenced the representativeness of some participants.

Despite its shortcomings, “the Arusha Agreement the Arusha accords were successful in bringing the country out of war” (Åberg, et al., 2008, p.27). This process provided the roadmap for the establishment of a transitional government, the integration of armed forces and power sharing. The institutional framework it created persisted and was widely implemented, eventually leading to the electoral dominance of a former rebel group, the CNDD-FDD, in 2005, which then negotiated the return of other movements. The road to full peace was long, involving separate and repeated ceasefire negotiations with non-signatory groups from 2003 to 2008 (Linekar, 2014). The challenge of reaching peace with the last active group, the Palipehutu-FNL, persisted years after Arusha. In the most African mediation process, Odendaal (2013) argues that national meditors are mediators able to usefully lead mediation in intra-state conflict, and this has proved to be successful in cases like South Africa (1985–1996), National Peace Council Ghana, Lesotho (2009–2012) arguing that “National mediation has succeeded when international actors have supported without interfering” (Odendaal, 2013, p.18). The Question here is to know, would the Burundi peace process be more totally fail, or be more succeful than it was if it was fully chaired by Burundian mediators?

The Arusha process was also an important moment for the participation of Burundian women, who campaigned for their inclusion with international support (Linekar, 2014). Although their participation was very limited, the presence of a few women in the negotiations in a patriarchal society like Burundi reflects an effort to make the process more representative of society, even if the main negotiators remained male political-military actors (Linekar, 2014). For example, “there were 126 delegates at the first round of negotiations in June 1998: two were women. This number increased slightly as delegations were later expanded to include more women. Seven women from civil society were present as observers from 1998, and they gained permanent observer status in 2000” (Linekar, 2014, p. 5). The process coincided with the drafting of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on women, peace and security, and the Burundian case was a useful example in this international context.

This paper provided a critical analysis of the Arusha Peace Process in Burundi showcasing both factors that contributed to its success and its weaknesses. While this process effectively brought together diverse political actors and established an inclusive framework, it notably failed to include other key armed rebel groups like the FNL and FDD, which undermined its ability to achieve immediate peace and prolonged violence. This implied that the conflict was not fully ready for cessation of hostilities at the time of the agreement. However, strong regional leadership from figures like Nyerere and Mandela, along with a well-structured mediation strategy, contributed positively to the negotiation’s outcomes. Despite these achievements, the lack of coordination among external actors and the exclusion of major rebel groups hindered this process. Even though the Arusha Peace Process laid a foundation for political transition, there are unresolved issues especially related to ethnicity (what others would call ethnic quotas) that necessitate further negotiations to achieve sustainable peace in Burundi.

Åberg, A., Laederach, S., Lanz, D., Litscher, J., Mason, S. J., & Sguaitamatti, D. (2008). Unpacking the Mystery of Mediation in African Peace Processes. Retrieved from https://peacemediation.ch/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Mediation_in_Africa_full.pdf

Bentley, K. (2004). Conflict In Burundi . Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/48602961.pdf

Kleiboer, M. ( 1996). Understanding Success and Failure of International Mediation. Retrieved 2012, from JSTOR: http://www.jstor.org/stable/174357

Linekar, J. (2014). Women in Peace and Transition Processes. Burundi (1996–2014). Retrieved from Incluisve Peace & Transition Initiative : https://www.inclusivepeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/case-study-women-burundi-1996-2014-en.pdf

Nantulya, P. (2015). Burundi: Why the Arusha Accords Are Central. Retrieved from Africa Center for Strategic Studies : https://africacenter.org/spotlight/burundi-why-the-arusha-accords-are-central/

Nathan, L. (2006). No Ownership, No Peace: the Darfur Peace Agreement. Crisis States Research Centre.

Odendaal, A. (2013). THE USEFULNESS OF NATIONAL MEDIATION IN INTRA-STATE CONFLICT IN AFRICA. Retrieved from Center for Mediaion in Africa University of Pretoria : https://centreformediationafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/mediationargumentsno3new.pdf